Don & Dame

Resistance through gender play in Caribbean culture

A young Walter Mercado, now the feature of the Netflix documentary Mucho Mucho Amor, looks at the camera defiantly. The image is arresting in its audacity; its uncompromising queerness. It offers no apology to the Puerto Rican culture from which he came that demanded outward displays of masculinity. Throughout his lifetime, Walter Mercado, the astrologer, actor, dancer, and writer, was a revelation.

Though repeatedly pressed throughout his life, Mercado, was steadfast in his refusal to be defined,

"I have sexuality with the wind, I have sex with life."

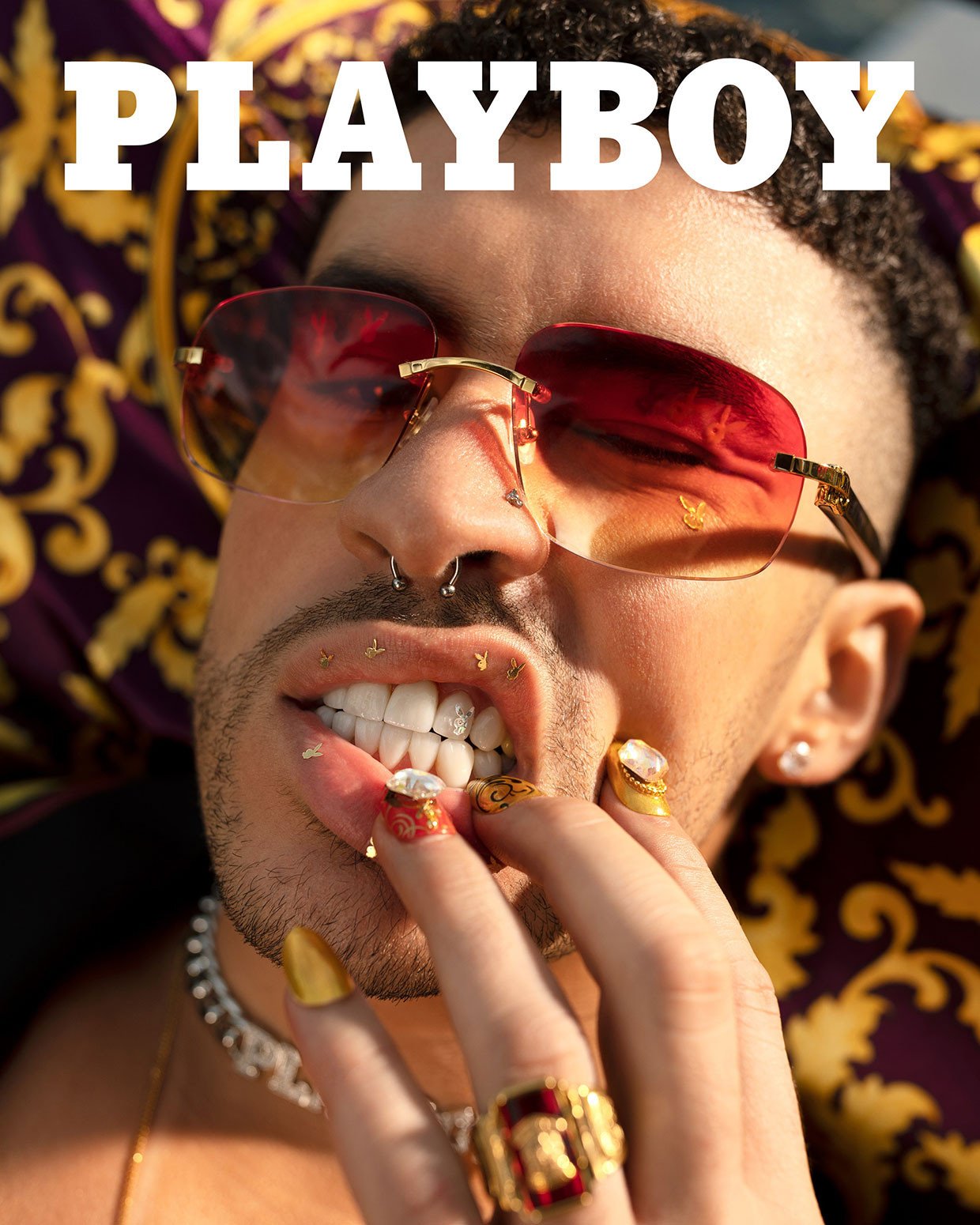

Less than a year after his death, we are not without his progeny. Shortly before the documentary aired, Playboy released is first digital issue featuring Puerto Rican artist Bad Bunny. Excluding the Playboy founder, Hugh Hefner, he is the first man to appear solo on the cover in the magazine’s history. In the now iconic shoot, Bad Bunny winks at his audience, nails bedazzled and lips flecked with miniature gold rabbits. He’s playing with us, but he’s not playing dress-up. This is Bad Bunny in full, take it or leave it; and we take it.

Bad Bunny making Playboy history as first-ever digital cover star, 2020

Though their gender variant style, both Mercado and Bad Bunny actively embraced a long legacy of play that defied gender roles. Clothing has always been political, and the Caribbean is no exception. Columbus’s arrival in the New World marked a new framework through which race, gender, color, class, and ethnicity were defined and then redefined through dress (or lack thereof). To possess this New World, Europeans actively strove to control and homogenize the politics of clothing, notions of sex and gender, and behavioral codes of first native populations, then enslaved people and then the indentured laborers who came from cultures that functioned according to different rules. In response, those same norms would to be upended, subverted and used as direct attacks on the colonial system that ruled the region.

One of the constitutive elements of Carnival is the notion of the world turned upside down, manifesting itself through different forms of cross-dressing. If, in Europe, the (mis)rule of carnival had a person of low rank impersonating someone of high status, in the Caribbean it is not difficult to imagine that slaves cross-dressed as slaveholders and other powerful figures of the colonial administration.

Characters such as the Loca, Dame Lorraine, and Mother Sally all of which are men in women's dresses with padded or exaggerated breasts and buttocks, make regular, traditional appearances in the annual Festival de Santiago Apostal in Loiza Aldea, Puerto Rico and the Carnival celebrations in Trinidad and Barbados, respectively. The dynamics of colonialism throughout the Caribbean have bred a unique form of masquerade and transvestism through which the boundaries between gender, race and class are simultaneously interrogated, problematized, and challenged.

Dame Lorraine, Rachel Pringle of Barbados

In Martinique or Guadeloupe, in direct opposition to the French model of marriage and family, le mariage burlesque parodies the idealized fiction of a heterosexual nuclear family unit. Each year on the first Monday of the Carnival, men and women perform each other’s conjugal role by cross-dressing as their gendered other. So the man masquerades as the (often pregnant) wife and – to a lesser extent – the woman dresses and performs as the husband. The happy couple is followed by a wedding procession and are “married” by a registrar and a priest along the Carnival route.

Yet in this context, where Eurocentric understandings of sexuality and gender are so often cut and pasted without attention to local histories and traditions, le mariage burlesque represents the contradiction imposed on French Caribbean citizens who continue to uphold a European (and heterosexual) model of marriage and family.

Tracing a history of cross-dressing Caribbean identities outside of Carnival performances, however, is much more difficult. The accuracy and seriousness with which the enslaved population embarked in cross-dressing is evident, but what is equally clear is the anxiety that such practices created in the white ruling classes and the latter’s resulting urge to diminish these performances. To this end, they were treated as naive folkloric expressions as opposed to the subversive acts and transgressive assertions of resistance and autonomy that they were.

Today, many Caribbean comedic careers are built around this idea of gender disruption as pantomime. Popular personalities such as Rohan Perry and Majah Hype, are widely recognized for their portrayals of Caribbean characters, particularly women. Using cheap or improperly positioned wigs, garish or no make-up and exaggerated gestures, these characters lean heavily on the trope of men dressed as women for amusement.

Majah Hype in character

While tolerated in the context of play and masquerade. the penalty for non performative cross dressing is as best mockery, at worst, imprisonment or death. Bereft of images that are dignified, nuanced and non performative, the overwhelming attitude throughout the Caribbean towards any form of gender disruption has been charged. The violence and hostility towards non conforming individuals remains deeply embedded in society.

In February 2009, four Guyanese transgender women were convicted for the offense of appearing in public as men in female attire. This violation falls under the 1893 Summary Jurisdiction Act section and its application disproportionately targets trans women and non conforming men. Promisingly, however, in 2018, the law was struck down by Guyana’s highest court. In 2015, Jamaica, well known for violence towards its queer community, held its first Pride Parade. A few years later, the Trinidad and Tobago High Court declared a law that criminalized homosexuality unconstitutional.

Throughout the Caribbean, however, much work is to be done towards the equitable treatment of those who challenge gender norms. For every Walter Mercado and Bad Bunny we celebrate, there are others; those who remain unprotected by fame, fortune or distance. For every magazine cover and documentary, there are a thousand stories of creating oneself that remain untold. They remain, and in doing so, they continue a tradition of resistance through form and self. In so doing, they redefine and recreate and possess a self that they are told they cannot have.

They possess it anyway.

From the documentary “Young and Gay: Jamaica’s Gully Queens”

photo by Christo Geoghegan

Recommended Reading

The Cross-Dressed Caribbean, Writing, Politics, Sexualities

Edited by Maria Cristina Fumagalli, Bénédicte Ledent, and Roberto del Valle Alcalá

The Queer Caribbean Speaks: Interviews with Writers, Artists, and Activists

Kofi Omoniyi Sylvanus Campbell

Re/Presenting Self & Other: Trans Deliverance in Caribbean Texts

Rosamond S. King

Callaloo; Vol. 31, No. 2 (Spring, 2008), pp. 581-599

Imagining the Invisibles: Cross-Dressing and Gender Play in the French Caribbean

Charlotte Hammond

Royal Holloway, University of London 2014

Erotic Islands: Art and Activism in the Queer Caribbean

Lyndon K. Gill